HOW WILL THE CORONAVIRUS IMPACT YOUR CONTRACTS?

By Brian J. Lamoureux & Joshua J. Butera

The coronavirus pandemic is unprecedented in our modern history and economy. Because so much of our business world revolves around contracts and the terms that parties use to make their agreements, the words they use matter. Two of those words that are becoming increasingly important are “force majeure.”

“Force Majeure” translates from the French as “superior force.” In essence, it is an external, uncontrollable, and substantial event or circumstance beyond a party’s control that prevents it from upholding its end of a bargain. By no means exhaustive, some typical example of force majeure events are: wars, riots, fires, floods, typhoons, earthquakes, hurricanes, lightning, explosions, strikes, epidemics, slowdowns/lockouts, prolonged shortage of energy or supplies, moratoriums, and acts of government that would prevent a party from performing its obligations.

“Force Majeure” translates from the French as “superior force.” In essence, it is an external, uncontrollable, and substantial event or circumstance beyond a party’s control that prevents it from upholding its end of a bargain. By no means exhaustive, some typical example of force majeure events are: wars, riots, fires, floods, typhoons, earthquakes, hurricanes, lightning, explosions, strikes, epidemics, slowdowns/lockouts, prolonged shortage of energy or supplies, moratoriums, and acts of government that would prevent a party from performing its obligations.

The touchstone of every force majeure event is that it is unanticipated, unavoidable and seriously affects a party’s ability to perform. For example, if an earthquake destroyed the area upon which a contractor was supposed to build an apartment building, the contractor would be excused from performing because it would then be impossible to perform that work. Or, if a party’s supplier of raw material could not ship that material due to say, an explosion or government shutdown, that likely would excuse that party from performing because it was unable (through no fault of its own) to obtain the necessary raw materials.1

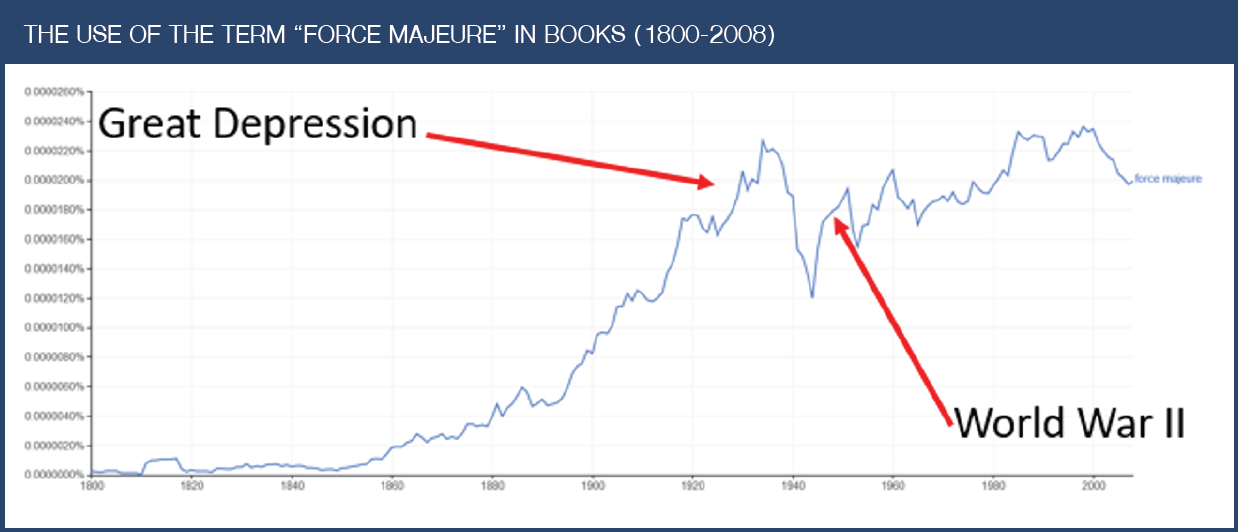

As the following chart shows, there were spikes in the use of the phrase “force majeure” in books during the Great Depression and World War II. This implies that during those devastating economic times, people were discussing and using force majeure as a way to excuse their performance under contracts. Given the serious shortages in food, raw materials, and other items during these times, supply chains were broken, thus preventing parties from having the material needed to either make or supply what they had promised under their contracts.

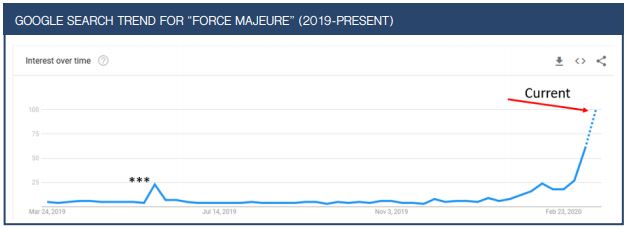

Unfortunately, due to the massive shutdown of manufacturing and supply in China during the coronavirus outbreak there, we have seen substantial material shortages that are rippling through the economy, particularly construction. As the Google trends chart below shows, there has been a rapid increase in the number of times the phrase “force majeure” is Googled. This suggests that parties are looking for ways to excuse their contractual performance in light of the coronavirus pandemic. It is also possible, too, that some buyers have been told by their suppliers that “due to force majeure events,” shipments are delayed or cancelled. And, these buyers, unfamiliar with the term, are Googling it to learn what it means. Either way, this search trend does not bode well for a rapid economic recovery when the pandemic is over.

***We believe this spike in searches for “force majeure” likely relates to major announcements by gas transmission companies in June, 2019 that there would be a four-day shutdown of natural gas delivery on a pipeline due to unanticipated repairs.

One increasingly important question is whether the coronavirus pandemic will constitute a force majeure condition that would allow a party to either curtail or excuse its obligation to perform under a contract. Because the last official pandemic was the Spanish Flu outbreak in 1918, it is unsurprising that there are no published court cases deciding whether a pandemic constitutes a force majeure event. Therefore, we must rely on the legal principles we already know about force majeure clauses.

First, whether a force majeure event will excuse a party’s performance will largely depend on the language of the contract. If the contract has a force majeure clause that includes pandemics as one of the qualifying events to invoke the clause, then a party will be on very solid footing to invoke the clause and excuse its performance. A force majeure clause may contain the helpful and important qualifying phrase of “including, but not limited to,” which would give some leeway to claim that the pandemic should be included as one of the reasons to excuse performance. However, to successfully invoke the coronavirus pandemic as a force majeure event, the party will still have to show that the pandemic did, in fact, cause the problem it was experiencing and that it was out of the party’s control. A party cannot simply rely on the pandemic declaration as a free pass to get out of all of its contractual obligations. There has to be a connection between the problem it is experiencing and the pandemic.

Second, courts will also consider whether the risk of nonperformance was foreseeable and whether the party could have mitigated that risk. For example, if a construction company’s supplier emailed the company in January saying that March’s shipments would be delayed, and the construction company did nothing to try and procure the supplies elsewhere, the construction company will likely not be excused from performing what it had promised another party to do, such as construct a building.

Third, the impacted party will have to show that performance is truly impossible. In many instances, force majeure events do not necessarily make performance impossible, but rather, they make performance more inconvenient or expensive. In those cases, a force majeure clause will likely not excuse a party from performance as courts have generally reserved force majeure events to those which truly and completely make performance impossible.

Fourth, even if a party’s contract does not have a solid or broad force majeure clause, look for language that excuses performance due to government action, order, law, or regulation. Given the flurry of shutdown orders, travel bans, social distancing measures and the like, it is possible that a party might be able to excuse itself from performance on that basis. For example, if a party was hired to organize and run a road race with hundreds of runners and the government banned gatherings of ten or more people, then that party would very likely be excused from any damages for not having conducted the race.

Finally, if your contract does not contain a force majeure clause, all hope is not lost. While it is true that a court will not import or “read in” a force majeure clause in a contract where none exists, courts sometimes excuse parties from performing under the traditional common law principles of “impossibility,” “commercial impracticability,” or “frustration of purpose.” These rules vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, so you should check your contracts to see what law applies to them.

Generally, these principles work as follows:

- Impossibility – Impossibility of performance occurs when a party is unable, under any circumstance, to perform its obligations under a contract. For example, if a contract requires a broker to sell a one-of-a-kind artwork and that artwork is subsequently destroyed by an unforeseeable fire, it is impossible for the broker to perform. The circumstances creating the impossibility could not have been anticipated, and the party seeking relief must have sought all practical alternatives to permit performance.

- Commercial impracticability – Commercial impracticability occurs when, unlike impossibility, it remains possible for an obligation under a contract to be performed, but the cost of performance is so unreasonably burdensome or excessive it is deemed to be impracticable. To invoke a commercial impracticability, an event must have occurred (not caused by the party seeking relief) that made performance impracticable and all parties to the contract assumed that such event would not occur. The coronavirus pandemic and related government actions are dramatically affecting all types of businesses, including the travel industry, the hospitality industry, construction industry, and business-to-business suppliers. While the effects of the virus and underlying facts are unique to each business, the pandemic is unquestionably making business more burdensome and more costly.Unfortunately, merely losing money on a contract or not making as much profit as one would have hoped is not sufficient to invoke this principle. Rather, a party must show (a) how the pandemic affected its ability to perform; (b) calculations that demonstrate how the cost of performance will actually damage the business; (c) why alternative action could not be taken or substitute provided; and (d) specific examples of efforts to mitigate losses that were nevertheless unsuccessful. Whether a performance can successfully be excused based on commercial impracticability is highly dependent on the factual circumstances.

- Frustration of Purpose – Frustration of purpose occurs when, through an unforeseeable event, the principal purpose of the contract is no longer possible even though performance is still possible and even practical. For example, parties may be relieved from performance under contract to advertise on a yacht during a yacht race when that race is canceled. The boat is still available to display the advertisement, but the entire purpose of the contract was to advertise at a specific event in front of more viewers. The principal purpose must have been known by both parties to the contract.

Key Takeaways:

1. Review your contracts now to determine whether you or the other party may be able to invoke a force majeure clause in the contract. Most contracts contain critical notice requirements and specific deadlines to provide that notice. If the other party invokes a force majeure clause or the pandemic as a means of trying to get out of its obligations to you, you should act swiftly and consult with counsel.

2. Document all of your efforts to perform under the contract.

3. Document all of your efforts to mitigate your damages or inability to perform, such as trying to procure materials or supplies elsewhere. Keep records of all instances where you are told that a material or supply item is out of stock or unavailable.

4. Even if your supply chain is still currently intact, keep a log or record of how the government’s shutdown orders and restrictions may be impacting your ability to perform your work.

5. Keep in mind that the force majeure door swings both ways. If you seek to use the current pandemic as a force majeure event to excuse your performance under Contract A, for example, you should be prepared to have another party you have a contract with use the same argument to excuse their performance to you under Contract B. Courts do not take kindly to parties making inconsistent arguments.

6. Pull out your insurance contracts and call your broker to determine what coverage you may have for business loss or interruption. Unfortunately, after the 2002-2003 SARS outbreak, many insurance companies began excluding coverage for viruses and bacteria. But, check your policies nonetheless.

For more information, please contact PLDO Partner Brian J. Lamoureux and Associate Joshua J. Butera at 401-824-5100 or email bjl@pldolaw.com or jbutera@pldolaw.com. Attorney Lamoureux is a member of the firm’s litigation, employment, corporate, and cybersecurity teams. Attorney Butera is a member of PLDO’s corporate and trust and estates teams.

Notes

- Note, however, that if the impacted party could have obtained that raw material elsewhere – albeit at a higher price or on less favorable terms – the likelihood of that party successfully invoking force majeure to excuse their performance is low.

Practice Areas

Advisories

Knowledge Library

Receive Our E-News

Client Review

“What is extremely unique about PLDO is that they are great lawyers who actually care about me and my business. They make me feel as if I am the most important client in the firm and I am certain that all of their clients feel the same way. ”

President, The Droitcour Company